Here are our programs in Geometry so far.

Flat Geometry

- Our challenge to get new results about very basic mathematics using at most second-year undergraduate mathematics has been met by a large number of new results about Heron’s formula. Including many new generalizations of Heron’s formula.

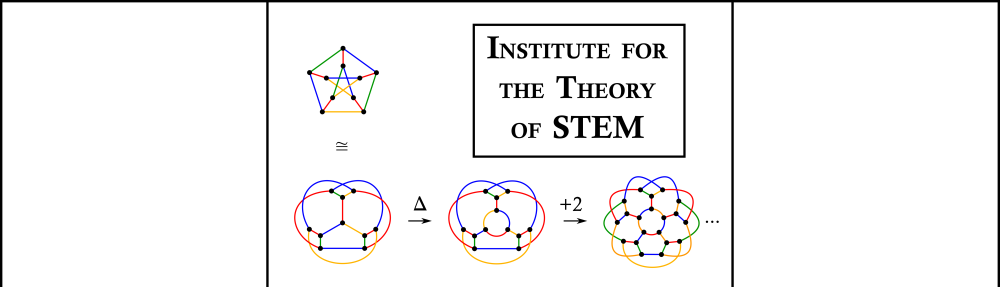

- That Apollonius’ Theorem about the length of a median, and Euler’s Quadrilateral Theorem, generalize to one theorem per eigencluster shape per N-body problem has also been supplied. Another name for eigencluster shapes is relative Jacobi coordinate vector shapes; these are in 1:1 correspondence with the unlabelled at-most binary tree graphs. The minimum case with a nontrivial theorem is the 2-path tree: the Apollonius case, uplifted from a triangle to a 3-body problem in arbitrary dimension. The Euler result is for the Jacobi-H coordinates for the 4-body problem, which correspond to the bent 3-path tree for the smallest at-most binary tree that is not a straight path. The first new Theorem is then for the Jacobi-K coordinates also supported by the 4-body problem, corresponding to the straight 3-path graph existing as a second at-most-binary tree on 4 vertices.

Pages 2 to 6 of the following explain this program a bit more, with references.

The above is an Accepted Review. The first two articles of the current program are here:

`Two New Perspectives on Heron’s Formula” (2024), https://wordpress.com/page/conceptsofshape.space/1244 (Accepted Article).

“The Fundamental Triangle Matrix” (2024),

https://wordpress.com/page/conceptsofshape.space/1306 (Accepted Article).

Subsequent articles are to be upgraded to take into account the following Accepted Article’s insights.

v2: improved notation and added references

Stewart’s Theorem generalizes Apollonius’ from medians to Cevians. We have now reproved this using moments methods, leading to generalizing it to one theorem per eigenclustering network.

3. We are also investigating the graph-theoretic content of contact and packing problems.

4. And why projective and discrete geometry’s graphs appear to be more interesting than those arising from the other branches of flat geometry.

Foundations of Geometry and Differential Geometry

- We are interested in the Killing equation of Differential Geometry. Solving this gives the isometries that the underlying manifold possesses. We are also interested in its generalization to the arbitrary group of continuous geometrical transformations. Some of examples of this are the similarity Killing equation, the affine Killing equation and the conformal Killing equation. See Yano’s book [1] for an introduction

- Stillwell [2] listed four pillars of (flat) geometry. Each is a foundational system from which flat geometry can be built without use of the other three pillars. The four pillars are 1) Euclid’s own ‘compass and straight-edge’approach, which is usually how flat geometry is taught in schools. 2) Linear Algebra, as came to dominate university teaching of flat geometry after around 1970. 3) The transformation group approach to flat geometry, also sometimes called ‘Kleinian’ or ‘Erlanger’. 4) The projective approach to flat geometry. These are usually taught without explanation of why they produce one and the same flat geometry, a gap that Stillwell brilliantly filled. There are more pillars of flat geometry, however, and the generalized Killing equation is a first such that is rooted in deeper Differential Geometry. Lie’s integral theory of geometrical invariants is another. Cartan’s differential theory of geometrical invariants is a third. And the Lie-Dirac algorithm provides a very new fourth, using brackets algebra consistency as a selection principle. This is in parallel to how the hitherto much more well-known Dirac algorithm for constrained dynamical systems works. One of us will be writing two books covering these four Differential Geometry pillars of flat geometry.

Arenas of Geometrical Objects

- We are interested in all arenas of geometrical objects. Arenas are the mathematical spaces formed by the totality of the objects in question. For the N-body problem, and thus also for the polygons, these coincide with well-known configuration spaces. Some other examples that occur in the above work are the arena of all triples of Cevians and various of its subsets, such as the arena of all invertible triples of Cevians and the arena of concurrent triples of Cevians. That the arena of all eigencluster shapes corresponds to the arena of all unlabelled trees gives a first indication of the common theme that studying arenas is very inter-disciplinary. The arena corresponding to one branch of mathematics’ objects often ‘belongs to’ a different arena of mathematics.

- Two arenas of geometrical objects that we are doing a lot of work with are the sphere of triangles modulo similarities and the complex-projective space CP^2 of quadrilaterals modulo similarities. At the topological level, these configuration spaces were discovered by Smale in 1970 . At the metric differential geometry level, they were found to carry natural metrics by Kendall in 1984. See the book [3] for a review. This gives us one reason to study CP^2 in depth, the triangle sphere being very nice to calculate with and yet non-generic in dozens of ways that we are documenting. Another reason is that the sphere S^2, incidentally equal to CP^1 , and CP^2 are also the space of qubits and of qutrits. And there are again many features by which the qutrit is the minimum nontrivial example of a qunit.

- Studying shape spheres and so on constitutes shape theory in the sense of Kendall. This refers to David Kendall, who, as a famous Statistician, applied knowledge of these spaces to giving a geometrical theory of Statistics; see [3] for a review. But the very same spaces appear in the N-body problem, of say Celestial Mechanics [4] or Molecular Physics [5]. In cases where scale is part of the modelling, we have the topological and metric differential geometry level cone over the corresponding shape space. Such work can also be qualified as relational, in the sense of Leibniz calling for a stripping from Physics of Newton’s notions of absolute origin and absolute axes. If one is using similarity shapes, one is also stripping away absolute scale.

- Relational analysis involves casting everything in terms of differences, ratios, and more advanced geometrical invariants as befits whatever geometrical group is being quotiented out. In Physics, this is fairly standard, if not formally packaged together into a detailed mathematical framework of its own. In Geometry, it has hitherto been somewhat less usual, though it is still to be understood in terms of choosing particularly useful adapted variables for each problem. We have however gone as far as conducting a relational analysis of basic Combinatorics, a subject which had never seen this before. See our Combinatorics program for details of this, and for a large amount of new work on the arenas of combinatorial objects as well.

- We also have an open program as regards reformulating various large areas of theoretical Computer Science in terms of relational analysis and arenas. If this sounds interesting to you, check this webpage again in 2025 for some publicly-declared progress.

[1] K. Yano, The Theory Of Lie Derivatives And Its Applications (North Holland, 1955) https://books.google.fr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=V97YDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Killing+Yano+1955+book&ots=GxbJoD-MG6&sig=ORhNDAXwbCebRTzoo75kiQe4wC8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2] J. Stillwell, The four pillars of geometry (Springer, 2010). https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/0-387-29052-4

[3] D.G. Kendall, D. Barden, T.K. Carne and H. Le, Shape and Shape Theory (Wiley, 1999). https://books.google.fr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=HLuCo2SrRRcC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=Kendall+Shape+Theory+book&ots=uQmhDJmVUe&sig=-5fLOpeMWKqmIr22X6I4UqIzIiA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Kendall%20Shape%20Theory%20book&f=false

[4] R. Montgomery, The three-body problem and the shape sphere”, Amer. Math. Monthly 122 299 (2015), arXiv:1402.0841. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.4169/amer.math.monthly.122.04.299

[5] R.G. Littlejohn and M. Reinsch, Gauge fields in the separation of rotations and internal motions in the N-Body Problem, Rev. Mod. Phys. 69 213 (1997). https://journals.aps.org/rmp/abstract/10.1103/RevModPhys.69.213.

We will say more about some of these Differential Geometry projects in 2025.